“If Ray was in love with his first lyrically young film, in the second it was more adult and mature…the final act, in Apur Sansar, is a restrained, deliberate bit of work…it comes firmly to grips with reality, and yet does so with tenderness and humanity.” Amita Malik

“If Ray was in love with his first lyrically young film, in the second it was more adult and mature…the final act, in Apur Sansar, is a restrained, deliberate bit of work…it comes firmly to grips with reality, and yet does so with tenderness and humanity.” Amita Malik With Sarbojaya’s death in Aparaito, Apu’s estrangement from his village, Nishchindipur, and the tradition of his ancestors is complete. Apur Sansar (The World of Apu) opens with its protagonist in Calcutta, with a graduate degree but jobless, and singularly devoid of any ambition. Living in a one room tenement near the railway tracks, with only his books and flute for company, Apu is idealistic and dreams of becoming a writer. The resemblance between the Apu of Apur Sansar and his literary counterpart is scant. “Ray’s Apu is here a nobler creation. He has dispensed with some of Apu’s contradictions, attenuated his narcissism and drawn him as someone of heightened sensitivity and refined emotion.” (Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye) Apu was the contemporary Indian man at the crossroads of tradition and modernity – a predicament that the Indian youth, grappling with the issues of a newly independent nation, could identify with.

For Soumitra Chatterjee, who dons the mantle of the adult Apu, the character symbolized the idealism shared by his generation – “We were to a great extent the Apus of our time.” (Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye) Chatterjee, whose acting experience included only amateur theatre in college, had approached Ray during the making of Aparajito but was rejected since he was too old for the role of a teenage Apu (later played by Smaran Ghosal). The actor went on to become a regular in Ray’s films, from Apur Sansar in 1959 to Shakha Proshakha (Branches of the Tree) in 1990. Chatterjee regards Ray as instrumental in changing the acting style in Bengali cinema. Since the actors were usually from a theatre background, their acting was heavily influenced by stage histrionics. “Ray’s films brought about a real change…actors began trying to be cinema actors.” (Soumitra Chatterjee in Marie Seton’s Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray)

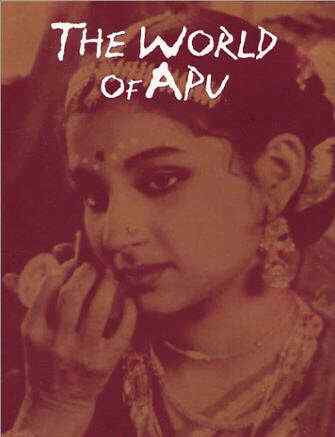

Apur Sansar also marks the debut of Sharmila Tagore. Tagore, who later became a major Bollywood star in the 1960s-70s, also acted in subsequent Ray films – Devi (The Goddess), Nayak (The Hero), Aranyer Din Ratri (Days and Nights in the Forest) and Seemabaddha (Company Limited). She was only fourteen when Ray ‘spotted’ her outside her school, St. John’s Diocesan. Sharmila is related to the more orthodox branch of Rabindranath Tagore’s family, and it took Ray considerable time and effort to convince her father. Though remarkably good, her performance in Apur Sansar was ‘heavily directed’. “Ray literally talked her through each shot: ‘Now turn your head, now look this way, now look that way, now look down, now come with your lines, pause here, and now come with your lines again.’” (Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye)

Like its predecessor, Apur Sansar owes more to Ray than to Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s novel. Eliminating the various other plot complexities, the film concentrates primarily on two aspects – the relationship between the struggling intellectual Apu and his uneducated wife, Aparna, and Apu’s reconciliation with his estranged son, Kajal. Unlike the film, Bandopadhyay’s Apu has a much wider contact with other girls before marrying Aparna. While in Benares, he becomes attached to Leela, the granddaughter of his mother’s employer. Later in the narrative, Leela is part of Calcutta’s charm that alienates Apu further from his mother. Failure to find a suitable girl had forced Ray to write off Leela from the narrative, a decision that he felt weakened the dramatic element in Aparajito. However, Leela’s absence is hardly felt in Apur Sansar. It is a simple and poignant tale of the idealistic Apu and his naïve child-bride, with the scenes between the newly married couple “one of the cinema’s classic affirmative depictions of married life.” (Robin Wood). What perhaps makes it all the more poignant is that they take place in the very same dingy one room apartment, where we had earlier seen Apu the bachelor, lying alone on a crumpled bed, playing his flute listlessly; there seems to be a new joie de vivre in Apu now.

Apur Sansar was conceived only after the completion of Aparajito and released in 1959, with Ray working on two other films, Jalsaghar (The Music Room) and Paresh Pathar (The Philosopher’s Stone) in the intervening years. Though the film’s fidelity to its literary source was a question of much debate and controversy, it was a commercial success in Bengal and won the President’s Gold Medal. The release of Pather Panchali and Aparajito in England, and then in America, had aroused interest among the international audience. However, the Venice Film Festival refused to screen the film in the competitive section on the grounds of its similarity to its predecessors – a decision supposedly influenced by the Festival’s director, F. L. Ammannati’s penchant for favoring Italian films. As a mark of protest, the London Film Festival, normally devoted to films that had won festival awards, invited Apur Sansar to inaugurate the Festival, awarded it the Place of Honor, and also the largest number of screenings. The film won the Sutherland Award for “the most original and imaginative film first shown to a British audience at the National Film Theatre.”

Apur Sansar also won the NBR Award for the Best Foreign Film, the Diploma of Merit at the Edinburgh Film Festival, and was nominated for the BAFTA Award. Edward Harrison, who had earlier distributed Pather Panchali and Aparajito in USA, screened the Apu Trilogy films as part of a single program in New York, lasting five and a half hours, with two breaks for coffee, thus giving the audience the opportunity to view the Trilogy as an unified work.

1 comment:

hey

Just saying hello while I read through the posts

hopefully this is just what im looking for looks like i have a lot to read.

Post a Comment